"Let’s use a token to secure this API call. Should I use the ID token or the access token? 🤔 The ID token looks nicer to me. After all, if I know who the user is, I can make better authorization decisions, right?"

Have you ever found yourself making similar arguments? Choices based on your intuition may sound good, but what looks intuitive is not always correct. In the case of ID and access tokens, they have clear and well-defined purposes, so you should use them based on that. Using the wrong token can result in your solution being insecure.

"What changes after all? They are just tokens. I can use them as I see fit. What’s the worst that could happen?"

Let’s take a closer look at these two types of tokens to better understand their role in authentication and authorization processes.

If you prefer, you can also watch this video on the same topic:

What Is an ID Token?

An ID token is an artifact that proves that the user has been authenticated. It was introduced by OpenID Connect (OIDC), an open standard for authentication used by many identity providers such as Google, Facebook, and, of course, Auth0. Check out this document for more details on OpenID Connect. Let's take a quick look at the problem OIDC wants to resolve.

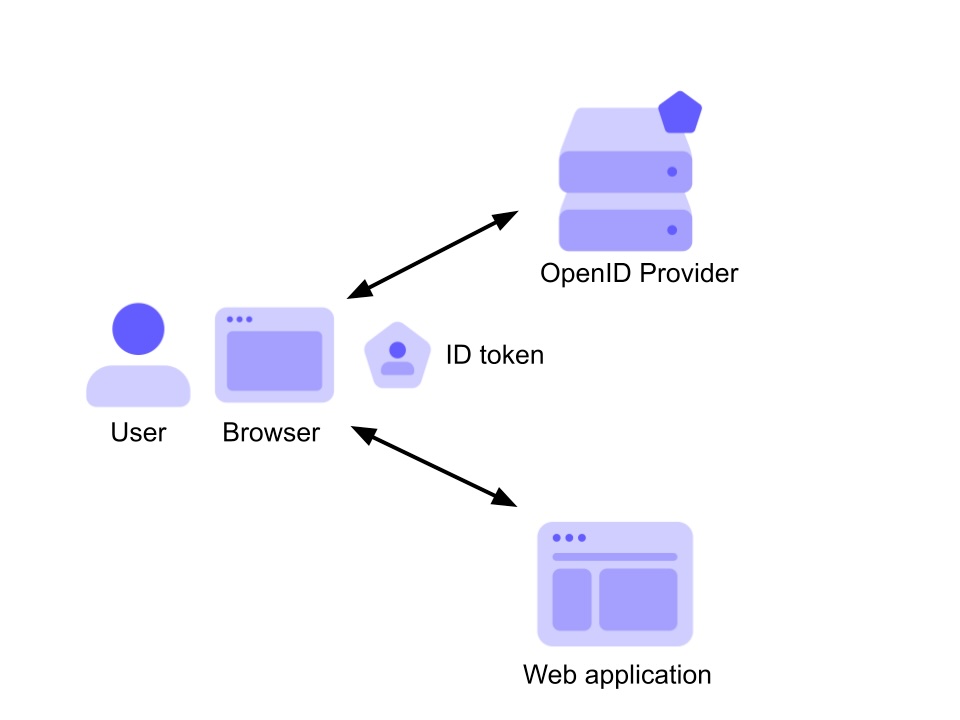

Consider the following diagram:

Here, a user with their browser authenticates against an OpenID provider and gets access to a web application. The result of that authentication process based on OpenID Connect is the ID token, which is passed to the application as proof that the user has been authenticated.

This provides a very basic idea of what an ID token is: proof of the user's authentication. Let’s see some other details.

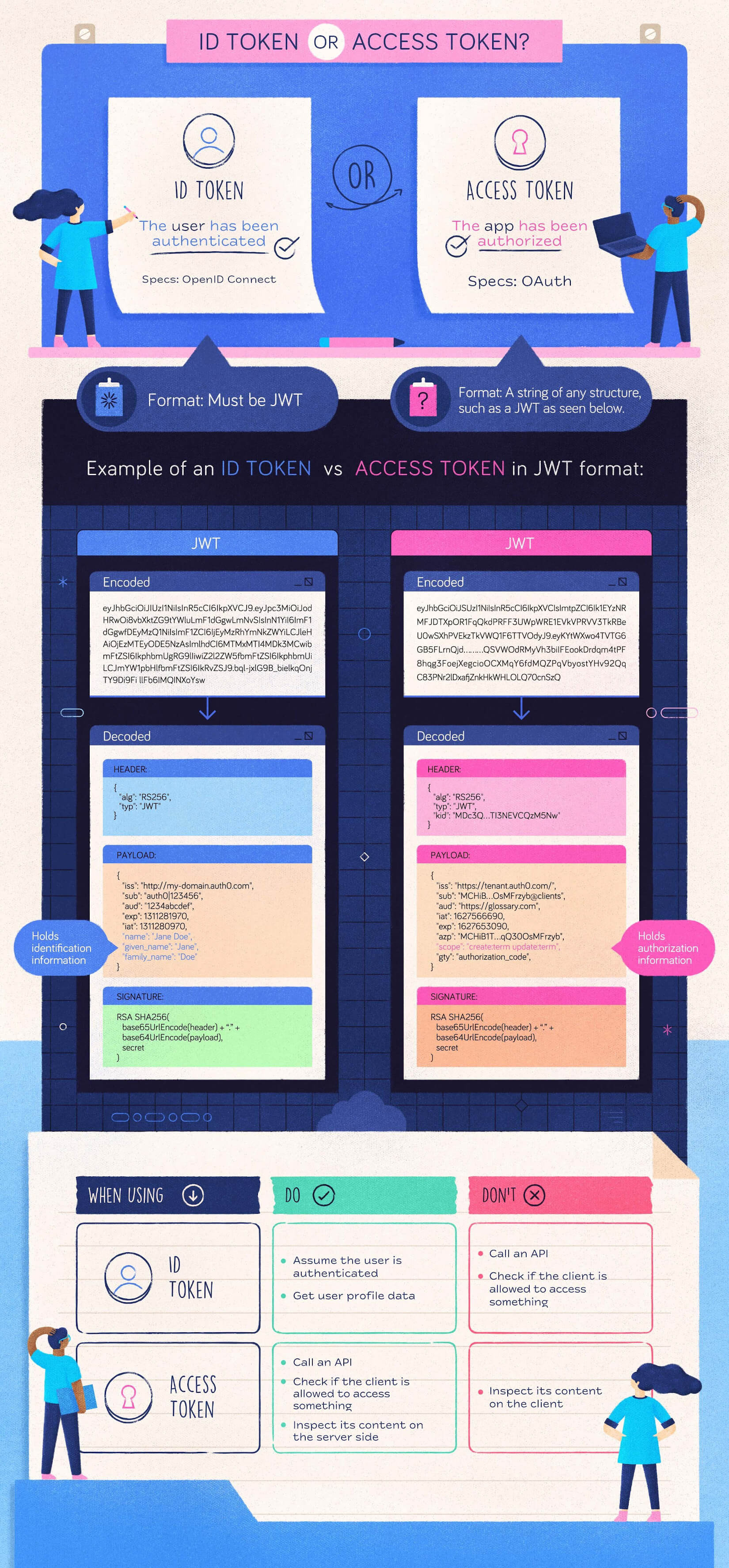

An ID token is encoded as a JSON Web Token (JWT), a standard format that allows your application to easily inspect its content, and make sure it comes from the expected issuer and that no one else changed it. If you want to learn more about JWTs, check out The JWT Handbook.

To put it simply, an example of ID token looks like this:

eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJpc3MiOiJodHRwOi8vbXktZG9tYWluLmF1dGgwLmNvbSIsInN1YiI6ImF1dGgwfDEyMzQ1NiIsImF1ZCI6IjEyMzRhYmNkZWYiLCJleHAiOjEzMTEyODE5NzAsImlhdCI6MTMxMTI4MDk3MCwibmFtZSI6IkphbmUgRG9lIiwiZ2l2ZW5fbmFtZSI6IkphbmUiLCJmYW1pbHlfbmFtZSI6IkRvZSJ9.bql-jxlG9B_bielkqOnjTY9Di9FillFb6IMQINXoYsw

Of course, this isn't readable to the human eye, so you have to decode it to see what content the JWT holds. By the way, the ID token is not encrypted but just Base 64 encoded. You can use one of the many available libraries to decode it, or you can examine it yourself with the jwt.io debugger.

Without going deeper into the details, the relevant information carried by the ID token above looks like the following:

{ "iss": "http://my-domain.auth0.com", "sub": "auth0|123456", "aud": "1234abcdef", "exp": 1311281970, "iat": 1311280970, "name": "Jane Doe", "given_name": "Jane", "family_name": "Doe" }

These JSON properties are called claims, and they are declarations about the user and the token itself. The claims about the user define the user’s identity.

Actually, the OpenID Connect specifications don't require the ID token to have user's claims. In its minimal structure, it has no data about the user; just info about the authentication operation.

One important claim is the

audRemember this small detail about the audience claim because it will help you better understand what its correct use is later on.

The ID token may have additional information about the user, such as their email address, picture, birthday, and so on.

Finally, maybe the most important thing: the ID token is signed by the issuer with its private key. This guarantees you the origin of the token and ensures that it has not been tampered with. You can verify these things by using the issuer's public key.

Cool! Now you know what an ID token is. But what can you do with an ID token?

First, it demonstrates that the user has been authenticated by an entity you trust (the OpenID provider) and so you can trust the claims about their identity.

Also, your application can personalize the user’s experience by using the claims about the user that are included in the ID token. For example, you can show their name on the UI, or display a "best wishes" message on their birthday. The fun part is that you don’t need to make additional requests, so you may get a little gain in performance for your application.

What Is an Access Token?

Now that you know what an ID token is, let’s try to understand what an access token is.

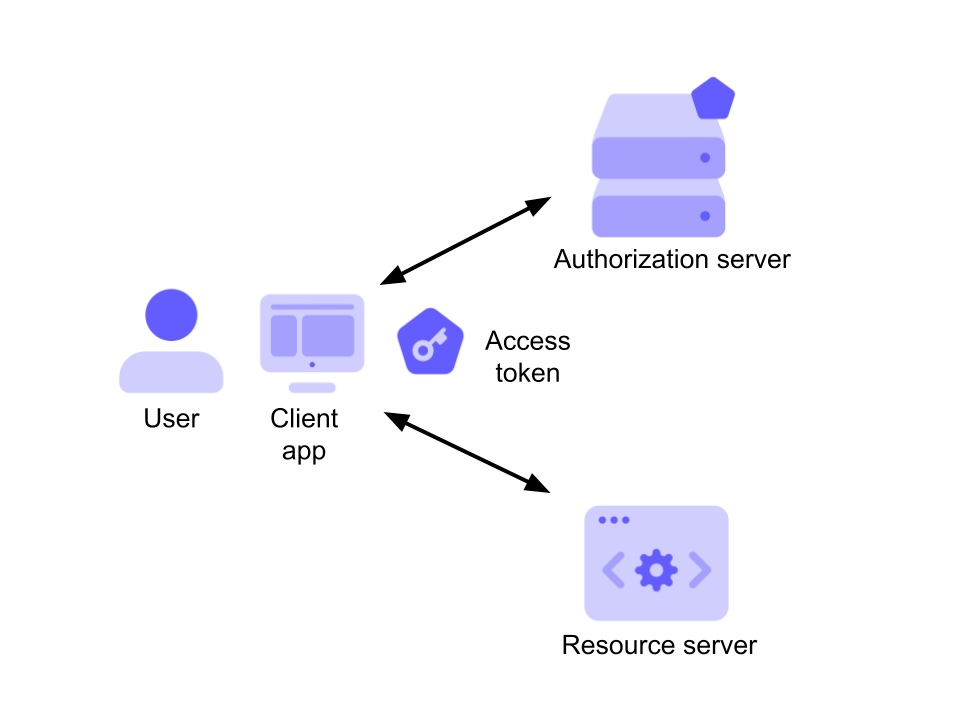

Let's start by depicting the scenario where the access token fits:

In the diagram above, a client application wants to access a resource, e.g., an API or anything else which is protected from unauthorized access. The other two elements in that diagram are the user, which is the owner of the resource, and the authorization server. In this scenario, the access token is the artifact that allows the client application to access the user's resource. It is issued by the authorization server after successfully authenticating the user and obtaining their consent.

In the OAuth 2 context, the access token allows a client application to access a specific resource to perform specific actions on behalf of the user. That is what is known as a delegated authorization scenario: the user delegates a client application to access a resource on their behalf. That means, for example, that you can authorize your LinkedIn app to access Twitter’s API on your behalf to cross-post on both social platforms. Keep in mind that you only authorize LinkedIn to publish your posts on Twitter. You don't authorize it to delete them or change your profile’s data or do other things, too. This limitation is very important in a delegated authorization scenario and is achieved through scopes. Scopes are a mechanism that allows the user to authorize a third-party application to perform only specific operations.

Of course, the API receiving the access token must be sure that it actually is a valid token issued by the authorization server that it trusts and make authorization decisions based on the information associated with it. In other words, the API needs to somehow use that token in order to authorize the client application to perform the desired operation on the resource.

How the access token should be used in order to make authorization decisions depends on many factors: the overall system architecture, the token format, etc. For example, an access token could be a key that allows the API to retrieve the needed information from a database shared with the authorization server, or it can directly contain the needed information in an encoded format. This means that understanding how to retrieve the needed information to make authorization decisions is an agreement between the authorization server and the resource server, i.e., the API.

OAuth 2 core specifications say nothing about the access token format. It can be a string in any format. A common format used for access tokens is JWT, and a standard structure is available. However, this doesn’t mean that access tokens should be in that format.

Alright! Now you know what an ID token and an access token are. 🎉 So you are ready to use them without any fear of making mistakes. But, wait. I do not see you convinced. 🤔 Maybe you need some other information. Ok. So, let’s see what these tokens are not suitable for.

What Is an ID Token NOT Suitable For?

One of the most common mistakes developers make with an ID token is using it to call an API.

As said above, an ID token proves that a user has been authenticated. In a first-party scenario, i.e. in a scenario where the client and the API are both controlled by you, you may decide that your ID token is good to make authorization decisions: maybe all you need to know is the user identity.

However, even in this scenario, the security of your application, consisting of the client and the API, may be at risk. In fact, there is no mechanism that ties the ID token to the client-API channel. If an attacker manages to steal your ID token, they can use it to call your API like a legitimate client.

For the access token, on the other hand, there is a set of techniques, collectively known as sender constraint, that allow you to bind an access token to a specific sender. This guarantees that even if an attacker steals an access token, they can’t use it to access your API since the token is bound to the client that originally requested it.

In a delegated authorization scenario where a third-party client wants to call your API, you must not use an ID token to call the API. In addition to the lack of mechanisms to bind it to the client, there are several other reasons not to do this.

If your API accepts an ID token as an authorization token, to begin with, you are ignoring the intended recipient stated by the audience claim. That claim says that it is meant for your client application, not for the resource server (i.e., the API).

You may think this is just a formality, but there are security implications here.

First of all, among other validation checks, your API shouldn’t accept a token that is not meant for it. If it does, its security is at risk. In fact, if your API doesn't care if a token is meant for it, an ID token stolen from any client application can be used to access your API. Of course, checking the audience is just one of the checks that your API should do to prevent unauthorized access.

In addition, your ID token will not have granted scopes (I know, this is another pain point). As said before, scopes allow the user to restrict the operations your client application can do on their behalf. Those scopes are associated with the access token so that your API knows what the client application can do and what it can't do. If your client application uses an ID token to call the API, you ignore this feature and potentially allow the application to perform actions that the user has not authorized.

What Is an Access Token NOT Suitable For?

On the access token side, it was conceived to demonstrate that you are authorized to access a resource, e.g., to call an API.

Your client application should use it only for this reason. In other words, the access token should not be inspected by the client application. It is intended for the resource server, and your client application should treat access tokens as opaque strings, that is, strings with no specific meaning. Even if you know the access token format, you shouldn’t try to interpret its content in your client application. As said, the access token format is an agreement between the authorization server and the resource server, and the client application should not intrude. Think of what can happen if one day the access token format changes. If your client code was inspecting that access token, now it will break unexpectedly.

A Quick Recap

The confusion over the use of ID and access tokens is very common, and it can be difficult to wrap your head around the differences. Maybe it mostly derives from not having a clear understanding of the different goals of each artifact as defined by the OAuth and OpenID Connect specifications. Also, understanding the scenarios where those artifacts were originally meant to operate has an important role in preventing confusion on their use. Nevertheless, I hope this topic is a little more clear now.

To recap, here is a quick summary of what you learned about what you can and can’t do with ID and access tokens:

If you want to see ID and access tokens in action, sign up for a free Auth0 account and start to add authentication and authorization to your applications in minutes with your preferred programming language and framework.

About the author

Andrea Chiarelli

Principal Developer Advocate

I have over 20 years of experience as a software engineer and technical author. Throughout my career, I've used several programming languages and technologies for the projects I was involved in, ranging from C# to JavaScript, ASP.NET to Node.js, Angular to React, SOAP to REST APIs, etc.

In the last few years, I've been focusing on simplifying the developer experience with Identity and related topics, especially in the .NET ecosystem.