According to the Verizon Data Breach Investigations Report, compromised passwords are responsible for 81% of hacking-related breaches. Needless to say, a key part of overall information security is securing your users’ passwords.

However, while there are a lot of conventional password security practices that seem intuitive, a lot of them are misleading, outdated, and even counterproductive.

That’s where the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) password guidelines (also known as NIST Special Publication 800-63B) come in. Although they’re required only for federal agencies, they’re considered the gold standard for password security by many experts because of how well researched, vetted, and widely applicable they are for the private sector.

In fact, many corporate security teams are already using the NIST password guidelines as a baseline to provide something even more powerful than policies: credibility. So if you’re looking for what actually works for password security in 2020, here’s what the NIST says you should be doing (in plain English).

New Password Creation Guidelines

Password security starts with the physical creation of that password. However, it’s not just your users’ responsibility to ensure their passwords are up to par — it’s also up to you to ensure that the passwords are strong enough (especially in light of how the FTC handled the TaxSlayer case).

Here’s what the NIST guidelines say you should include in your new password policy.

1. Length > Complexity

Conventional wisdom says that a complex password is more secure. But in reality, password length is a much more important factor because a longer password is harder to decrypt if stolen.

Here’s a great example of how password length benefits you more than complexity on a technical level:

This is why the NIST guidelines call for a strict eight-character minimum length.

However, additional research shows that requiring new passwords to include a certain amount of complexity can actually make them less secure. And that’s why NIST has also removed all password-complexity requirements from their guidelines.

For example, many companies require that users include special characters, like a number, symbol, or uppercase letter, in their passwords to make them harder to decrypt.

Unfortunately, many users will add complexity to their password by simply capitalizing the first letter of their password or adding a “1” or “!” to the end. And while it technically does make a password more difficult to crack, most password-crackers worth their salt know users tend to follow these patterns and can use them to reduce the time needed to decrypt a stolen password.

Additionally, as password complexity increases, users tend to reuse passwords from account to account, increasing the risk that they could be the victim of a credential stuffing attack if one account is breached.

So instead of forcing users to create more complex passwords, ask them to create longer ones if you want to improve password security.

2. Eliminate Periodic Resets

Many companies ask their users to reset their passwords every few months, thinking that any unauthorized person who obtained a user’s password will soon be locked out. However, frequent password changes can actually make security worse.

It’s difficult enough to remember one good password a year. And since users often have numerous passwords to remember already, they often resort to changing their passwords in predictable patterns, such as adding a single character to the end of their last password or replacing a letter with a symbol that looks like it (such as $ instead of S).

So if an attacker already knows a user’s previous password, it won’t be difficult to crack the new one. The NIST guidelines state that periodic password-change requirements should be removed for this reason.

Password Authentication Guidelines

The way you authenticate a password when a user logs in can have a massive impact on everything related to password security (including password creation). Here is what NIST recommends regarding the actual input and verification of passwords.

1. Enable “Show Password While Typing”

Typos are common when entering passwords, and when characters turn into dots as soon as they’re typed, it’s difficult to tell where you went wrong. This motivates users to pick shorter passwords that they’re less likely to mess up, especially on sites that allow only a few login attempts.

So if a user can choose, when alone, to have the password displayed during typing, they have a much better shot at entering lengthy passwords correctly on the first try.

2. Allow Password “Paste-In”

If passwords are easier to enter, your users are more likely to use a longer, more complex password in the first place (which is more secure). That’s where “paste-in” password functionality is now advantageous — if entering passwords is as simple as copying and pasting them into a password field; it encourages safer behavior.

This is especially important considering how many passwords the average person has to remember these days and the tools people are using to manage them all.

For example, a survey by NordPass found that 70% of people in the United States and the United Kingdom have more than ten passwords (20% have over 50). And many people have started using password managers to generate and store their passwords. So by allowing paste-in functionality this also allows people to use the auto-fill function of password managers to streamline the authentication process and stay safe at the same time.

3. Use Breached Password Protection

The new NIST password guidelines require that every new password be checked against a “blacklist” that includes dictionary words, repetitive or sequential strings, passwords taken in prior security breaches, variations on the site name, commonly used passphrases, or other words and patterns that cybercriminals are likely to guess.

Some platforms, like Auth0, take this to another level and check real-time login attempts against a blacklist, ensuring that users are protected even if their passwords are leaked publicly:

4. Don’t Use “Password Hints”

Some companies try to help users remember complex passwords by offering a hint or requiring them to answer a personal question.

However, with the constant dissemination of personal information on social media or through social engineering, the answers to these prompts are easy to find, making it easy for attackers to breach your user’s accounts. So this practice is now forbidden by the NIST guidelines.

5. Limit Password Attempts

Many attackers will attempt to breach an account by logging in over and over again until they figure out the right password (brute-force attack). And a great way to stop these kinds of attacks is to limit the number of login attempts that are allowed before locking the account.

The average attacker will need a lot more attempts than the average typo-prone user. So by including a cutoff or delay, you’ll drastically increase the amount of time an attacker will need to break in (to the point where it’s almost pointless to try).

6. Use Multi-Factor Authentication

Multi-factor authentication (MFA), also known as two-factor authentication (2FA), requires that users demonstrate at least two of the following in order to log in:

- “something you know” (like a password)

- “something you have” (like a phone)

- “something you are” (like a fingerprint)

The NIST guidelines now require the use of multi-factor authentication for securing any personal information available online. However, their guidelines are very specific on what qualifies as a valid form of authentication and what does not.

For example, in the new guidelines, email joins voice-over-internet protocol (VoIP) on NIST’s list of channels that are not acceptable for MFA because they’re not considered out-of-band (OOB) authenticators (they’re not truly a “separate channel” because they do not necessarily prove possession of a second device).

So even if you’re using two-factor authentication, you’ll want to review the NIST guidelines to ensure that the channels you’re using meet NIST standards.

The SMS Controversy

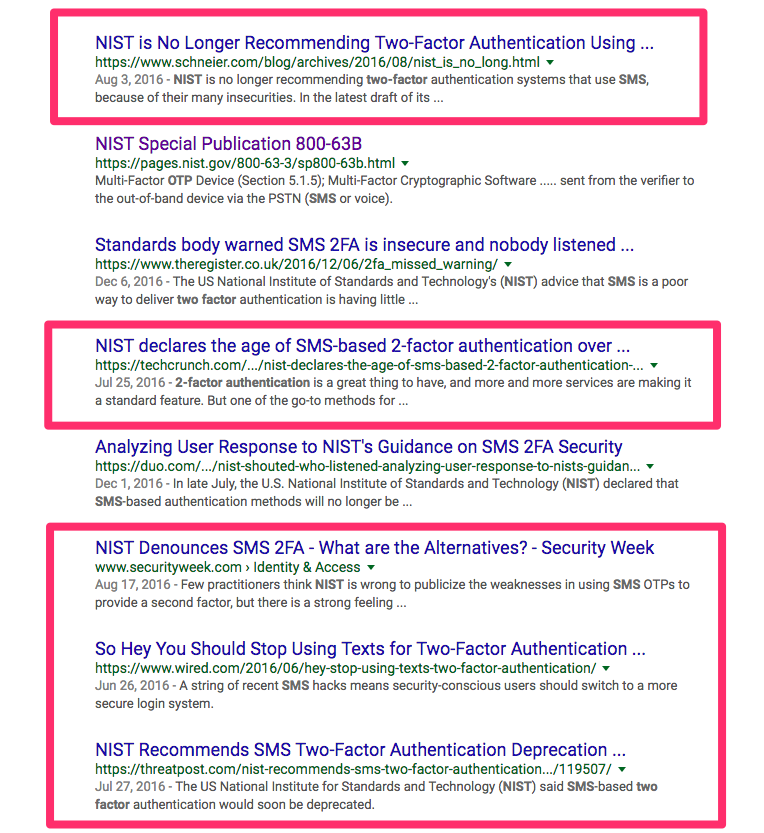

A previous version of the NIST password guidelines stated that using SMS as a second channel for authentication may not meet OOB requirements and could be disallowed in the future.

This led to a deluge of articles released by the security world declaring the death of SMS-based 2FA. However, the next revision of the NIST guidelines contained no explicit mention of SMS deprecation, leading to confusion.

After lobbying from the CTIA, NIST backtracked on its concerns, explicitly including SMS as a valid channel for OOB authentication.

Nevertheless, some concerns about SMS authentication remain valid. SMS channels can be attacked by smartphone malware and SS7 hacks. In addition, message forwarding and number changes mean that access to messages does not always prove possession of a device.

NIST has not ignored this uncertainty. Their guidelines do insist that authenticators make sure the user’s telephone number is associated with a specific physical device when SMS (or voice) 2FA is used. They further recommend that authenticators watch for behavior such as device swapping, SIM changes, and number porting, which could indicate a compromised channel.

However, the removal of recommendations against SMS indicates that this widely used 2FA channel is far from dead. It remains much more secure than email and is an effective way to reduce your reliance on passwords.

Password Storage Guidelines

Many security attacks have nothing to do with weak passwords and everything to do with the authenticator’s storage of passwords. Here’s what NIST recommends for ensuring passwords are stored securely.

1. Secure Your Databases

Your users’ passwords will be stored in a database (or several). So, to protect them, it’s important that access to these databases is limited to essential personnel only.

However, most companies’ databases aren’t as secure as you’d expect.

“The big thing that bothers me is when I go to a customer’s site. Usually, their [database] configuration is so weak that it’s easy to exploit. You usually don’t need buffer overflow or SQL injection [attacks] because the initial setup of the database is totally insecure,” Slavik Markovich, CTO of Sentrigo, told Dark Reading.

So to ensure that your users’ passwords are stored safely, you’ll want to ensure that your databases are secured from the most common attacks at all times.

Additionally, keep in mind that any authentication credentials your administrators use should follow the NIST guidelines as well since that’s how attackers often gain access.

2. Hash Users’ Passwords

Password database breaches are going to happen. However, you can still protect your users in the event they do by hashing their passwords before you store them. For example, Patreon’s databases were breached in 2015. But thanks to a strong hashing scheme (bcrypt), the attackers were unable to use the credentials they acquired because they couldn’t revert the password hashes to the original passwords.

The NIST guidelines require that passwords be salted with at least 32 bits of data and hashed with a one-way key derivation function such as Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2 (PBKDF2) or Balloon. The function should be iterated as much as possible (at least 10,000 times) without harming server performance.

In addition, they recommend an additional hash with a salt stored separately from the hashed password. That way, even if the hashed passwords are stolen, brute-force attacks would prove impractical.

Focus on User Experience to Improve Password Security

Cybersecurity and user experience are often at odds with each other. But the NIST password guidelines are pretty clear: strong password security is rooted in a streamlined user experience.

Your users will always do what makes their lives easiest (and research shows they’ll do so even if they know that behavior compromises their password security). So if you create the kind of user experience that uses this tendency to encourage safe behavior, it helps you both keep their data secure.

Want to learn more about finding the magical balance between UX and security? Check out this blog post that lays out our philosophy.

About the author

Diego Poza

Sr Manager, Developer Advocacy (Auth0 Alumni)